St John the Evangelist, open, is an astonishing interior, which I'll leave it to Pevsner to explain, contained by a decidedly odd exterior - naturally I loved it but I think St Nicholas in

Rushbrooke, Suffolk is superior.

Nicholas Ferrar was the son of a wealthy merchant. He was born in 1593 and studied medicine. He went abroad, to the universities of Padua and Leipzig, and returned home in 1618. He was a man of a mystic bent, impressed by the Cambridge Platonists, Juan de Valdes, and the Arminians. The idea of forming a religious community came to him in 1624. His mother felt as he did, and they decided to buy a house at Little Gidding. Nicholas Ferrar was ordained deacon in 1626. The community numbered about thirty to forty, and Nicholas’s brother John Ferrar with wife and two children and their sister with husband and sixteen children also joined. There was a school with three schoolmasters, and there were alms-people. The discipline was demanding, three services a day and only two meals for the adults, but no vows were prescribed. Nicholas Ferrar worked on Concordances or Harmonies of the Bible, i.e. biblical materials presented as consecutive stories. The books were written and bound by hand. Embroidery was cultivated too. The community was in close touch with George Herbert at Leighton Bromswold and Sir Robert Cotton at Conington. Charles I visited them three times, the last time on his flight. Bishop Williams of Lincoln also paid them a visit (from Buckden). Mrs Ferrar died in 1634, Nicholas Ferrar in 1637, and the nephew whom he had regarded as his successor in 1640. In the mood of the forties the community was decried as popish. In 1646 Little Gidding was attacked and sacked. The fifties saw the end.

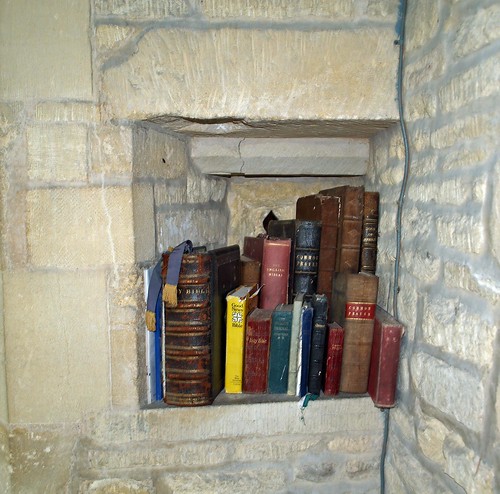

ST JOHN EVANGELIST. The community did not build a new church: they remodelled a dilapidated old one. Excavations in 1921 have shown that this old church was larger than the present one. Anyway the present church is very small. It consists of nave and chancel only. It lies with trees l. and r. looking into spacious fields and towards the gently rolling country. The building is of brick and only its facade is of stone. This facade is dated 1714. It is a strange facade, not in any Queen Anne tradition. If a big name were to be connected with its style, it would be Archer rather than Hawksmoor. The facade is quite narrow and has two giant angle pilasters with small obelisks on. The doorway has a kind of pilaster strips with sunk panels carrying big corbels for the straight hood instead of capitals. In the middle is a bellcote of rusticated pilasters, and on that a flat obelisk or steep pyramid with a ball finial and three mysterious pierced oblong openings. - The most interesting feature of the interior is the arrangement of the SEATING in the nave college-wise. This is decidedly a Puritan tradition, and one would like to attribute it to Nicholas Ferrar’s time. If so, it can only have applied to the church preceding this, and the argument that the household and other population was too big to allow for such an arrangement would only be fully valid if the dimensions of the preceding church were known. The STALLS in the nave have thick balusters and the backs high detached baluster-like columns carrying segmental arches. In the chancel the PANELLING has long balusters too. This may well be of 1714, in imitation to a certain extent of the time of Nicholas Ferrar. But can the stall-fronts also be 1714 and not c.1625? Or can they possibly be Clutton’s, who restored the church in 1853 and must have done the job extremely well? - REREDOS. One panel of the Jacobean reredos with one of the usual broad blank arches is now S of the altar. - The present REREDOS of brass tablets with the Creed, the Commandments, and the Lord’s Prayer dates from c.1625. - Also of c.1625 the FONT, a brass baluster with a delightful brass cover surrounded by a kind of crown. - Of the same time also the HOURGLASS STAND. - But the CANDLE SCONCES of slender turned balusters, extremely well grouped, are an exceedingly good Arts and Crafts job of c.1920, designed by W. A. Lee. - The LECTERN is the one medieval piece in the church. It is of brass, of a well-known East Anglian type, of the late C15. The same moulds were used for the lecterns of e.g. Urbino Cathedral and Oxburgh in Norfolk. It was presented by Nicholas Ferrar and is a splendid eagle, the moulded stem is splendid too, and the little lions at the base are pretty enough. - CHANDELIER. Little Gidding is a confusing church. This piece of a familiar Baroque type is of 1853. It might just as well be 1753. Is it perhaps a copy of a predecessor? - STAINED GLASS. Probably of 1853. The Crucifixion in the E window still has the ‘pre-archaeological’ glaring colours and pictorial composition. - EMBROIDERED cushion cover of the Ferrar Community. - Also three BOOK-BINDINGS. - PLATE. C17 Paten on foot; Flagon of 1629-30; Almsdish of 1634-5; C17 Crucifix.

LITTLE GIDDING. Small as it is, it has entertained a king, and has precious memories of a company of saints, who came to live here about the time the king was crowned. They made Little Gidding famous not only for their piety but for their delicate craftsmanship, examples of which we may all see here or in the British Museum.

They found only a crumbling manor house here, and a tiny church used as a barn, but it was as lonely then as it is today, and that is what Nicholas Ferrar wanted. He made the house his home and restored the church, and here his whole family came during the plague in 1625, staying on to live a community life of devotion and worship. With Nicholas were his mother, his brother’s family, his sister’s family (nearly a score of children), and three schoolmasters, the servants bringing the number to over forty. In all England there was not a more serene community; in no family were prayers more continuously or more devoutly said. The life was almost monastic, and it amazed and delighted Charles Stuart when he came to see the books they bound here and ordered two for himself. The first time the king came (he came three times) the whole family went out to meet him in a field still called King’s Close, and marched with him to the little church. At this old farmhouse the king once slept when his life was in danger.

Of the Little Gidding house hardly a stone is left, and the pigeon house which Nicholas cleared of its pigeons for the school has also tumbled down; but lonely in the field is the tiny church to which the family procession brought the king in 1633. The whole household proceeded to the church twice a day, two by two, a procession lengthened on Sundays by about 100 children from neighbouring villages - the Psalm Children they were called, for each one able to recite a psalm received from Nicholas Ferrar a penny and a Sunday dinner with the household. By the church is a little wood, and in it have been found traces of a flagged path Nicholas had made from this church to Steeple Gidding, a quarter of a mile away.

The church, with a stone front and a brick nave, is an odd little place from the outside, the 19th century west front all doorway and bell-niche topped by a pyramid; but inside it has a gracious charm, and still keeps much that Nicholas and his mother gave it 300 years ago. On the door is still the tiny brass plate, a few inches square, on which we can still decipher the words put there by them, the House of Prayer. They found it filled with hay and left it as complete and charming as a little church can be; and though it was much damaged by the Parliament men, who mistrusted the Royalist Ferrars and their devotions, and though the nave was shortened and shorn of its aisle in Queen Anne’s day, we seem here back in the world of that peaceful community as we stand in this narrow place, a church like no other.

A row of seats runs all the way round the church, their backs supporting rich oak arcading against the panelled walls, the nave seats arranged like the choir stalls, 15 on each side. The congregation sit facing each other across the narrow aisle, a plan we have only come upon once or twice. Very handsome are these arcaded walls, and the fine oak roof. The south wall is probably as in Nicholas Ferrar’s day, but the north wall has been made to match.

It is in the small sanctuary that we feel most intimately near the spirit of this place, for here is still the simple cedar wood altar table at which the rector would administer communion to his people and at which his king would kneel; and on the wall near by hangs a panel of the original reredos which was found in pieces some years ago. There is no pulpit now, but in Ferrar’s time, when the church had a transept, there was room for one, and on the wall near the old hourglass stand, where the nave and chancel meet, is a small cross made from the timbers of the old pulpit.

At the back of the altar now are the brass panels which were here in those days; it was Nicholas and his mother who set them on the wall: the Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Creed, all beautifully engraved on brass. They gave the brass lectern with its eagle and the three lions at its foot, and it may be that they ordered a local blacksmith to make the iron hourglass stand with scrolled ornament. We know that Little Gidding’s greatest treasure was their gift, a brass font thought to be unique. It is an elegant possession, its small bowl raised on a handsome stem and covered with a brass lid with piercing cresting, the top engraved with crosses and fleur-de-lys. The church also has a flagon engraved: “What Edwyn Sandys bequeathed to the remembrance of friendship his friend hath consecrated to the honour of God’s service.” There is a chair in the church made from old oak in the 17th century style.

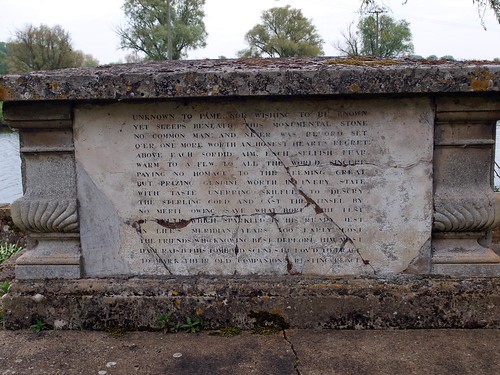

Other reminders of the Ferrar community are the Stuart arms beautifully embroidered by the ladies of the manor; two pieces of tapestry once used as book-rest covers, and a Book of Meditations with a rich embroidered binding such as has made the Little Gidding community famous in the book world. Here also is a deed bequeathing a pound a year to the poor, with Nicholas Ferrar’s signature still plain to see.‘ His grave is outside, under the altar tomb before the west door, and between him.and the door is the sunken grave of the brother who brought his family to join this loving community at Little Gidding, surely the most blessed spot in England in the turbulent days before the Civil War; and the pound a year (eight halfcrowns) is still distributed in the parish of Steeple Gidding to which it was bequeathed.

The Little Company of Saints

NICHOLAS FERRAR, who brought his saintly family to‘ Little Gidding and set them binding books between their prayers and praises, was the son of a London merchant who had Drake, Raleigh, and Sir John Hawkins among his friends. But the mind of this small boy, born in 1592, was set on religion and learning rather than adventure. He was not yet six when he lay awake one night tormented with doubts of God, and, having wandered into the garden to wrestle with his soul, flung himself on the frosty ground acknowledging God and vowing to serve him always. That vow he kept through his brief life, though not till he came to Little Gidding could he fulfil it as he wished.

So persuasive was his tongue that his Cambridge tutor was heard to exclaim: “May God keep him in a right mind, for if he should turn heretic he would make work for all the world; I know not who would be able to contend with him.” Scholars all over Europe became acquainted with this brilliant man when the doctors ordered him to travel and he went on a tour of foreign universities. He had to walk most of the way back from Madrid because his money did not arrive, and it was his safe passage through lawless country which led him to dedicate his life to God. He might have taken one of the richest heiresses for his wife, but excused himself for the sake of his vow, and settled down to the life of devotion he longed for. He bought the manor of Little Gidding in 1624, and was ordained deacon. His influential friends offered him rich livings, but he explained that he sought no advancement, and had only been ordained that he might minister to the needs of his community. That community was a family one, including his old mother, his brother John with his wife and three children, and his sister Susanna Collett, with her husband and 12 children. These, with three schoolmasters and the servants, all settled in the manor house of Little Gidding to a life of routine which made religious devotion the first duty. Their daily services, their prayers and psalms, their vigils through the night, were as continuous and as strictly regulated as in a monastery. There were watchings each night in the house chapels, the women in one, the men in another, and the whole household rose at four in summer and five in winter.

Everyone in the community was expected to learn a trade. Out of his great store of knowledge Nicholas taught medicine to his nieces, who tended the sick and put aside two rooms as dispensary and infirmary. That they had time for needlework we may see by their gifts to the church, but we must go to the British Museum if we want to see the finest art produced by this small company of saints, for here the books they bound are displayed as some of the best examples of 17th century craftsmanship. Nicholas engaged a bookbinder to teach the family; and himself wrote essays and stories and compiled Harmonies for them to bind. One of those Harmonies was a blending of the four Gospels into a chronological whole, his nieces cutting out the passages as he directed and neatly pasting them to make a patchwork book. Nicholas presented one to his friend George Herbert, and when the king came to Little Gidding to see their work he borrowed a Harmony for a few days.

As is the way of book-borrowers, the king clung to it for months, making notes in the margin in his own hand, and returning it with a request that the young ladies of Little Gidding should make him one. Mary Collett was the niece chosen to make the elegant binding for the king’s book, which we may see in the British Museum. Charles also begged Mr Ferrar to make for him a Harmony of Kings and Chronicles, as he was sorely puzzled over these two accounts of the Old Testament kings. This Mr Ferrar did, his young nephew Nicholas binding it in purple velvet, and from Little Gidding to the king went out this fragment consolation in the troubled days when the Civil War was brewing.

The old mother and Nicholas himself both died before the waves of war broke over the heads of this devoted company. They had longed for nothing better than to live in peace with their neighbours, but for long they had been persecuted by many who called their devotion popery. A pamphlet was circulated protesting against the Monastical Place called the Arminian Nunnery at Little Gidding; and in 1646 the day came when they had to flee from the approach of military zealots; who ransacked the house and spoiled the church. Little Gidding saw its company of saints no more, and two years later the king who had delighted in their books walked out on to the scaffold.