ST MARY. Perp mostly. But the chancel is late C13, with geometrical tracery, Y-tracery, and similar forms in the windows which are framed inside by giant blank arcading. The coarse PISCINA is late C13 too. The W tower is Dec, though the date 1635 appears over the door. It has set-back buttresses, a doorway with continuous mouldings, pairs of transomed two-light bell-openings, a nice frieze over, and no spire. The arch towards the nave has castellated capitals. Dec also the S doorway, with continuous mouldings too. But the arcades of five bays are Perp, with piers of the standard moulded section and two sunk waves in the arches. Also Perp the four-light aisle windows with uniform panel tracery, the clerestory windows, and the ornate s porch with niches l. and r. of the entrance and a small third niche above the entrance arch. The latter contains the lily-pot of the Annunciation. Good nave and aisle roofs with stone corbels. - FONT. Octagonal, with pointed quarrefoils etc. - ROOD SCREEN. Dec, of one-light divisions, the doors each with two ogee arches carrying a circle with flowing tracery. - The STALLS have MISERICORDS, the best in the county. They represent (a) a man writing - a Knight and lady with a shield - an animal, (b) a carpenter - a man and a woman haymaking (wool-combing?) - a sheep shearer, (c) a woman gleaning - a man reaping and a woman with a sickle - sheaves of corn. - COMMUNION RAIL. Jacobean. Imported into the church. - SOUTH DOOR. With bold Dec tracery. - STAINED GLASS. Much of Kempe & Tower; none of much interest, considering the late dates. - PLATE. Cup of Britannia silver, 1721-2; Cup, 1724-5 ; undated Paten on foot; undated Plate; Flagon, 1743-4; late C16 German brass Almsdish with the Annunciation and stags and hounds, engraved. --MONUMENTS. Sir John Bernard Robert d 1679. According to Gunnis by William Kidwell, c..1690. It has a remarkably good bust on top. - J. and T. Miller d 1681 and 1683. Cartouche tablet in the tower. - Mrs Jackson d 1689. Slab in the S aisle. She was Pepys’ sister, the last of the Pepys family in the parish.

BRAMPTON. It leads us on to the ancient county town, but it bids us pause on the way. It has delightful cottages, a 17th century inn, and a stately house in a hundred acres of woodland where Hannah More would often walk with Lady Olivia Sparrow. But whoever comes here is thinking of our most famous and charming busybody, and of the things he saw when he found time to run away from London and come to Brampton for a quiet day.

He was Samuel Pepys. He was born in London, but his uncle Robert (and later his own parents) lived at Pepys Farm, the white gabled house with tiny dormers near the church, home of John Drinkwater in our time. In this lovely spot the Diarist’s parents sleep. The house he knew as a boy and as a man has something of the 16th century, and the garden has rare memories of him, for it was here he dug up £1300 he had buried when London was a heap of ashes and everyone was afraid of a Dutch invasion. Of this gracious place he writes in his immortal diary that he came to see the garden with his father and he blessed God he “was like to have such a pretty spot to retire to.” Though he did not come to end his life here, he spent many happy days at Brampton, and there is a quaint entry in his diary telling us that he was here in the summer of 1661 and that he walked up and down the garden talking with his father about a husband for his sister. “We must endeavour to find her one now,” he says, “for she grows old and ugly.”

We may be sure Pepys never came to Brampton without, chatting with everyone he chanced to meet. He would ask for the news, and would enquire about crops and cattle, and talk about the great doings in London; and, being a regular churchman, he must have heard a few sermons in the church. He would walk about in the great barn next door, and must have stood a thousand times to stare at the scene from the road, with his own house, the old barn, and the lovely church tower beyond. The church is magnificent. There is much here almost as Pepys saw it. Its chancel is 13th century and its nave 15th, and it stands nobly by the river Ouse, its 17th century tower among the limes. The arcade has lofty arches, the nail-studded north door is 15th century, and the timbers of the south door are enriched with a moulding of flowing tracery 400 years old.

The beautiful oak screen is 14th century; so is the font, on which is carved a rose and a shield. In the chancel are three 14th century stalls. The roofs over the nave and aisles are 15th century and have faces of men and animals among foliage, the beams resting on stone corbels with angels looking down. There is a 16th century almsdish engraved with the Annunciation, and a border round it showing hounds chasing stags. The altar rails are 17th century. On a monument is Sir John Bernard in his Stuart wig.

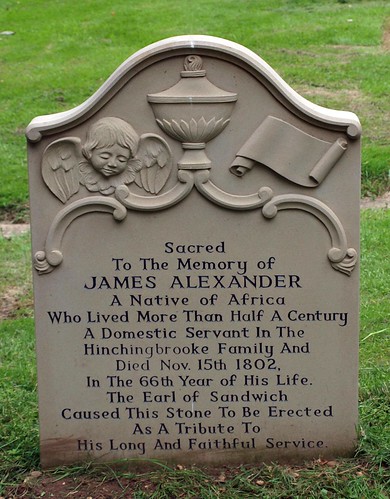

One of the chapels has an altar frontal with flowers, birds, and cherubs painted on wood by a 17th century Italian artist; and among the beautiful work of our own time is the chancel floor with its grey and white crosses planned by an architect who copied the design from one he saw as a boy in Ypres Cathedral. An oak screen has been made by village craftsmen, a fine piece of work with the shields of the Montagus, one of whom was the first Earl of Sandwich kinsman and friend of Pepys. There is much modern glass, one window in memory of Brampton’s heroes, with figures of Richard Lionheart, Gabriel, Michael, and Joan of Arc, and small scenes of the War below; and a noble Jesse window in memory of the 8th Earl of Sandwich, showing David with his harp, a Madonna, Edward the Confessor, St George, Hugh of Lincoln, and Etheldreda.

Brampton rightly treasures its three 14th century stalls, for they have come back after being for a long time in a Cambridge museum, one more example of the happy tendency for museums to return things to their proper places. It may be that Pepys sat in one of these stalls. Certainly he must have seen them and thought them very odd. They have misereres, and among the queer carvings is a monk with an inkpot, a- man and wife reaping with sickles, and a gleaner with a pile of sheaves. One of the most remarkable is a man mowing with a scythe, his wife gathering up the hay with a rake. Another shows a woodcarver at his bench, and another has a weaver with a roll of cloth, his shears as big as himself.

Pathetic is the inscription to Paulina Jackson, who died in 1689.She was the last Pepys to live at, Brampton, and was the ugly sister for whom Samuel tried to find a husband. He seems to have been successful, for Paulina was married to John Jackson of Ellington, and it was to her son that Samuel left his fortune.

He was Samuel Pepys. He was born in London, but his uncle Robert (and later his own parents) lived at Pepys Farm, the white gabled house with tiny dormers near the church, home of John Drinkwater in our time. In this lovely spot the Diarist’s parents sleep. The house he knew as a boy and as a man has something of the 16th century, and the garden has rare memories of him, for it was here he dug up £1300 he had buried when London was a heap of ashes and everyone was afraid of a Dutch invasion. Of this gracious place he writes in his immortal diary that he came to see the garden with his father and he blessed God he “was like to have such a pretty spot to retire to.” Though he did not come to end his life here, he spent many happy days at Brampton, and there is a quaint entry in his diary telling us that he was here in the summer of 1661 and that he walked up and down the garden talking with his father about a husband for his sister. “We must endeavour to find her one now,” he says, “for she grows old and ugly.”

We may be sure Pepys never came to Brampton without, chatting with everyone he chanced to meet. He would ask for the news, and would enquire about crops and cattle, and talk about the great doings in London; and, being a regular churchman, he must have heard a few sermons in the church. He would walk about in the great barn next door, and must have stood a thousand times to stare at the scene from the road, with his own house, the old barn, and the lovely church tower beyond. The church is magnificent. There is much here almost as Pepys saw it. Its chancel is 13th century and its nave 15th, and it stands nobly by the river Ouse, its 17th century tower among the limes. The arcade has lofty arches, the nail-studded north door is 15th century, and the timbers of the south door are enriched with a moulding of flowing tracery 400 years old.

The beautiful oak screen is 14th century; so is the font, on which is carved a rose and a shield. In the chancel are three 14th century stalls. The roofs over the nave and aisles are 15th century and have faces of men and animals among foliage, the beams resting on stone corbels with angels looking down. There is a 16th century almsdish engraved with the Annunciation, and a border round it showing hounds chasing stags. The altar rails are 17th century. On a monument is Sir John Bernard in his Stuart wig.

One of the chapels has an altar frontal with flowers, birds, and cherubs painted on wood by a 17th century Italian artist; and among the beautiful work of our own time is the chancel floor with its grey and white crosses planned by an architect who copied the design from one he saw as a boy in Ypres Cathedral. An oak screen has been made by village craftsmen, a fine piece of work with the shields of the Montagus, one of whom was the first Earl of Sandwich kinsman and friend of Pepys. There is much modern glass, one window in memory of Brampton’s heroes, with figures of Richard Lionheart, Gabriel, Michael, and Joan of Arc, and small scenes of the War below; and a noble Jesse window in memory of the 8th Earl of Sandwich, showing David with his harp, a Madonna, Edward the Confessor, St George, Hugh of Lincoln, and Etheldreda.

Brampton rightly treasures its three 14th century stalls, for they have come back after being for a long time in a Cambridge museum, one more example of the happy tendency for museums to return things to their proper places. It may be that Pepys sat in one of these stalls. Certainly he must have seen them and thought them very odd. They have misereres, and among the queer carvings is a monk with an inkpot, a- man and wife reaping with sickles, and a gleaner with a pile of sheaves. One of the most remarkable is a man mowing with a scythe, his wife gathering up the hay with a rake. Another shows a woodcarver at his bench, and another has a weaver with a roll of cloth, his shears as big as himself.

Pathetic is the inscription to Paulina Jackson, who died in 1689.She was the last Pepys to live at, Brampton, and was the ugly sister for whom Samuel tried to find a husband. He seems to have been successful, for Paulina was married to John Jackson of Ellington, and it was to her son that Samuel left his fortune.

No comments:

Post a Comment