The gate to the churchyard appears to be normally bicycle chain locked [slightly pointless since the wall is knee high] and a notice in the porch says something along the lines of "we really want you to visit our church, you can find the key 200m to the right (?) of the church" - is that facing it or with your back to it or possibly sideways? Not much help as directions go and after walking around the immediate vicinity for about 15 mins I gave up and decided to head home.

I might have considered a revisit until I read this - tbh it doesn't seem worth the effort.

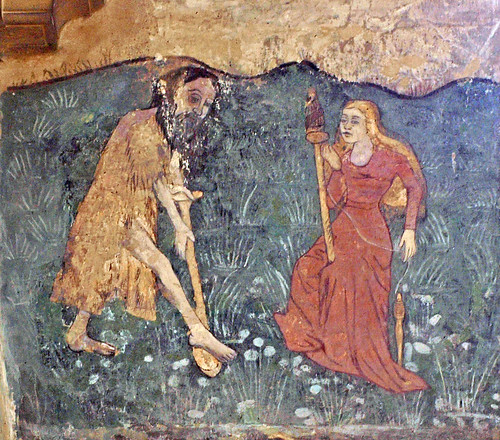

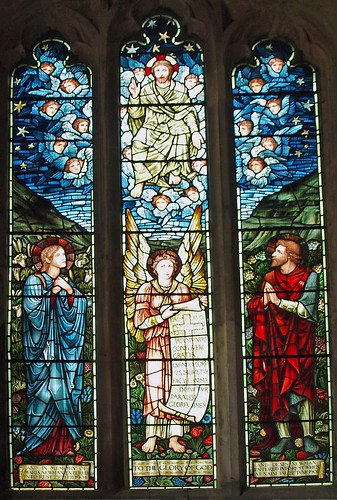

ST MARY. Rubble and brown cobbles. The amazing thing about the church is that it has a polygonal apse which is a genuine Dec piece. That, as everyone knows, is an extreme rarity in England. The windows are small and of two lights. Dec also the arches from the tower into the embracing aisles; they have three wave mouldings. The tower carries a recessed spire. Perp the high four-bay arcades with a typical pier section. The chancel arch matches. The four-centred aisle windows, another unusual trait (of East Anglian origin), are internally placed under much broader blank arches. So here - which is also not at all usual - the whole of nave and aisles is one unified design. The nave roof stands on good stone corbels, mostly of angels with shields or musical instruments. - FONT. Perp, octagonal. Panelled stem, quatrefoiled bowl, big flowers and also a Green Man on the underside. - SCREEN. Three divisions of the dado kept under the tower. Two are painted crudely with St George and the Dragon and St John Baptist. - STAINED GLASS. In the apse by Wailes, 1851. - PLATE. Chalice and Cover of 1569; Paten on foot inscribed 1693; Plate of 1702; Flagon of 1705; undated Salver.

BLUNTISHAM. Here lay a Roman god for 1500 years till his small bronze figure, inlaid with silver, was picked up near the Ouse and taken to the British Museum. Now its oldest possessions are the church, a 16th century inn, a row of 17th century houses, and an earthwork set up in the Civil War a mile away in the neighbouring hamlet of Earith. It lies between two “cuts” made by the Duke of Bedford in the 17th century as part of an attempt to solve the drainage problem. The rectory has a doorway brought from Slepe Hall, a house at St Ives which once belonged to Cromwell, and is now replaced by a school.

It is the church which draws the traveller to this place, where we look across ten miles of meadows to the noble tower of Ely. It has an apse unique in the county, most surprising from the outside, triangular, its three walls, crowned with gables, giving it a quaint appearance. The windows have flowing tracery, and between the gables are curious gargoyles. Graceful inside and out, the apse gives character to the 14th century chancel, with its fine south windows and its 15th century arch; but the interior of the apse is spoiled by the poor glass in the windows.

There is a handsome 14th century tower, its graceful spire enriched with 12 windows. The 15th century nave has splendid arcades with lofty arches. Its roof is as old as the walls it rests on, and among the stone corbels under it are musical angels and a man with a scroll.

The roof of the north aisle is nearly 500 years old, and rests on stone brackets with a bearded man and a crowned an gel among the carving.

Lovely things abound in this grand old church. There is a tall font with a bowl carved in the 15th century, its flowers, leaves, and grotesque heads very quaint. There are medieval tiles in the south aisle, and among much carved oak is a door made 400 years ago and an altar table by a 17th century carpenter.

One of the most precious possessions of the church is a fragment of its ancient screen, three panels made 500 years ago, and interesting for what is left in them of paintings by a 15th century artist showing through the work of an artist a century after him. Here is John the Baptist among flowers, and a fine St George with plumed headdress. He is riding a white horse, and seems to have two lances.

It is the church which draws the traveller to this place, where we look across ten miles of meadows to the noble tower of Ely. It has an apse unique in the county, most surprising from the outside, triangular, its three walls, crowned with gables, giving it a quaint appearance. The windows have flowing tracery, and between the gables are curious gargoyles. Graceful inside and out, the apse gives character to the 14th century chancel, with its fine south windows and its 15th century arch; but the interior of the apse is spoiled by the poor glass in the windows.

There is a handsome 14th century tower, its graceful spire enriched with 12 windows. The 15th century nave has splendid arcades with lofty arches. Its roof is as old as the walls it rests on, and among the stone corbels under it are musical angels and a man with a scroll.

The roof of the north aisle is nearly 500 years old, and rests on stone brackets with a bearded man and a crowned an gel among the carving.

Lovely things abound in this grand old church. There is a tall font with a bowl carved in the 15th century, its flowers, leaves, and grotesque heads very quaint. There are medieval tiles in the south aisle, and among much carved oak is a door made 400 years ago and an altar table by a 17th century carpenter.

One of the most precious possessions of the church is a fragment of its ancient screen, three panels made 500 years ago, and interesting for what is left in them of paintings by a 15th century artist showing through the work of an artist a century after him. Here is John the Baptist among flowers, and a fine St George with plumed headdress. He is riding a white horse, and seems to have two lances.