Pevsner, for one, thinks I'm wrong!

ST JOHN BAPTIST. Without any doubt one of the most rewarding churches in the county, with interesting work of all periods, none more interesting than that of the early C11 W tower. The exterior has irregular long-and-short quoins, the familiar thin, unstructural lesenes or pilaster strips, starting in quite an insouciant way even on top of arches or triangles, windows with arched and triangular heads, the typical unmoulded block-like abaci, the flat bands placed parallel with jambs and arch of an opening but at some distance from it, and in addition the most curiously moulded tower arch, an example of how unstructural Late Saxon architectural detail was. One ought to observe specially how, between capitals and abaci of the responds (if these terms can be used), the moulding recedes and rounds the corner instead of forming an angle. The form is almost streamlined. At least as noteworthy the decorative slabs outside the tower with scrolls branching off a stem symmetrically to the l. and r. and birds, one a cock, at the top.* The original entrance into the tower was from the S. The W recess can never have been more than a recess, as one of the lesenes runs up the wall outside behind it. The S doorway is now blocked inside by the work done in the C13. This consisted of an internal strengthening e.g. by a rib-vault on corbels (single-chamfered ribs leaving a large bell-hole open) and the addition of the octagonal upper part of the steeple. Two big bell-openings of two lights with round arches, triple-shafted jambs and a pierced spandrel (i.e. the Y-motif), low broaches and, standing on them, tall, plain, polygonal angle pinnacles, short spire, or perhaps rather steep-pitched octagonal roof. If it is called a spire it must be one of the earliest in England. The angles of the Saxon nave, which was aisleless, can also still be seen. It was a little wider than the nave is now. In the SE angle a mysterious small arched niche which looks almost as if it had been a piscina. The Saxon roof-line appears on the E wall of the tower.

The Norman style is missing, except for a capital and a head, re-set in the former rood stair in the S aisle.

Next in time come the N aisle and N chapel. The chapel is of one bay. The capitals of the responds indicate a late C12 date. The arch is round but double-chamfered. The arcade is of three bays and has slender circular piers and crocket and volute capitals with small heads.** Square abaci with the corners nicked. Round arches, still with zigzags on the wall surface and at r. angles to it. The N doorway still has a waterleaf capital. So the date of all this is probably the late C12. Small clerestory windows are visible from inside the aisle. Only a little later the S aisle and S porch. The arcades now have fine quatrefoil piers with subsidiary shafts in the diagonals and shaft-rings. The capitals have upright stiff-leaf. The arches are still round but have many fine mouldings. The S porch is a superb piece, tall and gabled with a tall entrance flanked by three orders of columns with stiff-leaf capitals. Pointed arch with many mouldings. The sides inside with tall blank arcading again with stiff-leaf capitals. S doorway with once more three orders, stiff-leaf capitals, and a round arch with many mouldings. The stiff-leaf is all early, that is upright with separate single stems. So the date will be within the first twenty years of the century. An odd rib-vault rises right into the gable (single-chamfered ribs). Shortly after the completion of the porch work must have started on the tower, and must have continued slowly.

The chancel dates from c.1300-30. At the same time the S aisle was widened E of the porch. Pretty windows with segmental arches and ballflower above them. Simpler Dec the windows in the aisle wall W of the porch and in the chancel. The chancel E window, however, is a true showpiece: five steeply stepped lancet lights and below the arch of each light a cusped arch with a crocketed gable over - a very rare motif (but cf. Milan Cathedral, late C14). Of the same phase the chancel arch, the SEDILIA (hood-mould on heads and also one head with arms held up), the PISCINA (pointed-trefoiled arch leaning forward, as they do above the heads of C13 effigies, and crocketed gable), and also the N aisle windows. Perp vestry of two storeys, Perp S chapel (Walcot Chapel) with richly decorated parapet and battlements. Quatrefoil frieze at the base. Simple windows. Very wide arch to the chancel. In the E wall brackets and very tall richly panelled canopies for images.

FURNISHINGS. FONT. C13. Octagonal. Leaf decoration in segmental lunettes at the foot of the bowl and also as a top band. In between single flowers. The supports are pointed-trefoiled arches of openwork with continuous mouldings. - SCULPTURE. Seated Christ in Majesty, relief, Late Saxon and of exquisite quality. The draperies are managed as competently as never again anywhere for a century or more, and the expression is as human, dignified, and gentle as also never again anywhere for a century. - Annunciation, under a canopy, S13 chapel. The message is carried on rays emanating not from the angel but from the Trinity. Late C15. - STAINED GLASS. Many windows by a former rector, Marsham Argles, one dated 1873. They are remarkably good. - PLATE. Cup and Paten, 1569; Almsdish, 1683; Cup, Paten, and Breadholder, silver-gilt, 1707. - MONUMENTS. Cross-legged Knight, defaced (N chapel). - Lady of c.1400; this must have been of fine quality (N chapel). - Grey marble tomb-chest, with recess above and cresting. The recess has a straight lintel on quadrants. Early Tudor (S aisle). - Similar tomb with recess of temp. Henry VIII to a member of the Walcot family. Richly quatrefoiled tomb-chest, recess and four-centred arch. The arch is panelled inside. The back wall has one big shield and above it diapering. Top cresting. - Francis Whitestones d. 1598 and family. Signed (a rare thing at the time) by Thomas Greenway of Darby; 1612. With two groups of small kneelers.

Barnack was known throughout the Middle Ages for its quarries. Peterborough Cathedral is built of Barnack stone. So is e.g. Ely Cathedral. The quarries were exhausted in the C18.

* One such bird also now below an image bracket in the S aisle E wall.

** On one capital an entwined serpent.

BARNACK. It was the home of a vigorous people a thousand years ago. It has seen the Saxons and the Normans and has cherished their work for us as part of our English heritage. If as part of that heritage the name of Charles Kingsley lives in some of the noblest pages of our literature, we owe a debt to Barnack for that too, for this was the home of the Kingsleys a hundred years ago. Here at his father’s rectory (now called the Old Rectory) Charles lived for six years until he was eleven. It is not possible that a mind like his, drinking in the spirit and tradition of our old land as a thirsty man drinks water, should have been here in his formative years and remained unmoved by the appeal of this old tower, one of the four Saxon towers of Northamptonshire.

He must have been stirred by these ancient stones, the simple windows and doorways, and the judge’s seat inside the tower, where. we may sit today with the light falling through a Saxon window above us and look at this old church through the arch the Saxons made. Here Charles Kingsley’s two brothers were born, and here Charles became a poet. All through his life he kept the impressions made on him by this Fenland scene.

From the end of our first thousand years of history has come old Barnack Tower. The Normans preserved it but fashioned the church according to their own ideas, and the English who were fast absorbing their Norman invaders transformed the Norman church through all our great building centuries, and made it what it is. All these years the tower has stood unchanged, except that the Normans raised it another storey and the English gave it a stone steeple. It is certain that there is Danish influence in its carvings.

The Saxon tower rises in two stages with the familiar pilaster strips of stone running to the top on all sides. The stages are divided by a triple stringcourse, and above this on three sides are magnificent examples of Saxon carving, three rich panels of acanthus leaves in relief, all three with a bird on the top, and three other panels of ropework set in window openings. The lower stage has on the south a pure Saxon doorway, and above it a rounded window capped by a square moulding with two birds in the spandrels. The west window is one of the simplest Saxon windows we have seen, made up of seven stones crudely put together, but still as their builders left them a thousand years ago. Above this window is a much-worn head.

It was the Normans (doubtless working with the English that followed them) who added the third stage to the tower, an octagon with double window openings packed within eight-sided buttresses. The arches of the openings are all finely worked, each with three orders set on slender columns, a line of carving running up alongside each outer column. Over these arches a fine corbel table runs round the tower, and above it rises the sturdy-looking 13th century spire, completing as perfect a piece of Norman and Saxon work as we could desire.

The tower is as captivating within as without. The rough stones remain as the Saxons placed them, and in the west wall is a recessed stone seat which was brought to light in the middle of last century when the accumulated rubbish of many generations was removed. It is framed with great stones as used in a Saxon window, and it is believed that this seat is an old bench of justice, perhaps the oldest magistrate’s seat known in England, used by the President of the Court when justice was administered in this tower. In front of us as we sit in the old seat is the fine Saxon arch looking into the nave. lt is raised on simple stones in the true Saxon way, and the arch of two plain orders rests on the crudest of capitals; but it has stood while all the magnificence of our cathedrals has been rising in the land.

It is good to come into this church by its south porch, which is considered one of the best porches in all England, with its high pitched and vaulted roof covered with heavy stones, its wall arcades, and its lofty pointed entrance arch with finely moulded shafts and richly decorated capitals. It leads us to a great round doorway with dainty English shafts, elegant capitals, and row upon row of moulding in the arch. This noble porch was built by the English who followed the Normans. On the wall is a scratch dial.

The church carries on the traditions of architecture through all the styles it has known in our countryside, from the simplicity of Saxon days, through the grandeur of the Normans, into all the phases of our three English building centuries. In the nave the north arcade is 12th century and the south arcade is 13th, as is also the extraordinary clerestory, very low and with only a few small trefoil windows. The chancel is 14th century and its chantries are 15th.

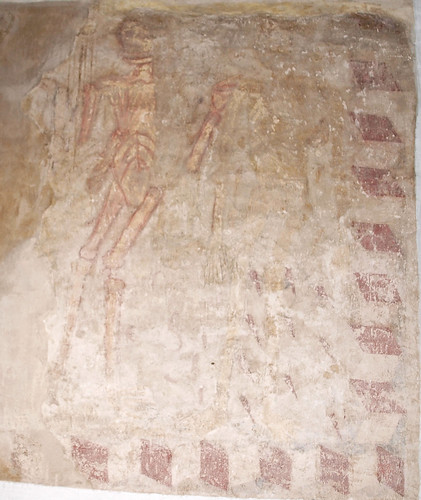

The lofty northern arches of the nave are carved with the zigzag of the Normans, and their foliage and faces are on the capitals; the south arcade is Norman and English, still with the round arches that were passing away, but with the clustered columns and the stiff foliage capitals of the first English builders. Simple Norman carving is on their arch between the chancel and the north chapel. In the middle of the wall of the south aisle is a recessed tomb with fleur-de-lys, and on the wall of the north aisle is a medieval stone relief of Our Lord in Majesty, three feet long, the robe of a finely diapered pattern and still bearing traces of colour; it was found under the floor, and is an impressive piece of craftsmanship.

In the chancel is a triple sedilia with a curious sculpture on the moulding of the arch, a grimacing head with arms thrown back to grip the stone. The piscina here (among several medieval ones) has elaborate 14th century carving. On the north wall of the chancel is a Jacobean monument with painted figures of Francis Whetstone’s family at prayer; he died in 1612. The east window has in the tracery a few fragments of original glass, almost lost among the modern panels. There is a little more old glass in the priest’s room, showing a pope wearing a triple crown, a king, and a youth in a big collar. A good modem window in the south chapel has the Madonna in blue with a red robed and green-winged Gabriel below her.

The north and south chapels, added in the 15th century, both have ancient sculpture in them. In the south chapel, on the left of the east window, is a niche with a rare stone carving of the Annunciation, three figures in the clouds sending rays to the heart of the Madonna, who is kneeling at a prayer desk. It is a striking group set in a canopy, and has a village scene with a church in the distance. In another canopied niche on the right of this window is a modern Madonna and child. The altar table of the chapel is Jacobean, and is carved with the names of the Fallen in the First World War. In the north chapel is a tomb with carved and painted figures of a knight and his lady from Elizabethan days, and in another recess of this chapel are two battered figures 600 years old.

The font is unusual in shape and commands attention by its profusion of carving by the first English craftsmen. It is 13th century, and stands on eight open arches, looking rather primitive, as if the new style were struggling into being. Round the sides of the bowl are stiff rosettes, eight pairs, and above and below them are two bands of foliage. The cover is carved at its eight angles and crowned by the small figure of a child angel, with wings as big as itself. The pulpit and the screen are modern, the pulpit a good imitation of 14th century tracery, the screen with gilded figures of Mary and John, and a fragment of a medieval screen worked into it.

The church is built, of course, of Barnack Stone from the famous quarries known to the Romans and worked from the days of the Caesars until the end of the 15th century, when the Barnack Rag was exhausted. It was said in the old days that

Peterborough Minster would not have been so high

If Barnack Quarry had not been so nigh.

It is not surprising that in this quaint village the cottages should have medieval work built into them. One 14th century house has carved rosettes and another has a Saxon window.

The Kingsley Brothers

ALL the world knows Charles Kingsley and his Westward Ho! but his two younger brothers, though both brought distinction to the family, are less known. George Henry was born at Barnack Rectory in 1827 and Henry in 1830. We come upon Charles at Eversley in Hampshire where he lies. George entered on an adventurous life while still in his teens, and was wounded during the barricades in Paris in the revolution of 1848. He came back to England and at 21 was fighting an epidemic of cholera. His brother tells us of it in his novel Two Years Ago, where George Kingsley is Tom Thurnall. George was a brilliant talker, a keen sportsman, an enthusiastic field naturalist; and as he was familiar with many languages he travelled widely, and in his 65 years explored as many countries as almost any man of his time. He did much good literary work also, especially in editing manuscripts, and has another claim to fame as the father of the famous Mary Kingsley, who wrote so finely of her travels in West Africa and gave up her life as a nurse in a South African hospital at the time of the Boer War.

His brother Henry was a novelist and an editor during his 46 years, and he, too, travelled far, for he went to Australia when he was 23 and enjoyed his adventures in the Mounted Police. He wrote about twenty books, in which he put much of his experiences of the wild life of Australia, and few of our novelists have more faithfully sketched the best type of an English gentleman. His books are permeated by a fine spirit of romantic chivalry, and in this sense keep the high tone of Charles Kingsley’s books. As a journalist he went through the first war in which Germany attempted to subdue Europe, and after Sedan, when Napoleon the Third and his army were captured, Henry Kingsley was the first Englishman to enter the town.

A Founder of English Literature

GEORGE GASCOIGNE, sleeping in the vault of the Whetstones at Barnack, was one of the founders of English literature. Born at Cardington in Bedfordshire in 1525, he compressed into his 52 years activity enough for half-a-dozen men. A kinsman of Martin Frobisher, he shared the restless energy of his wonderful age, and plunged into the excesses that ruined many brilliant young men in Tudor London. But he had a scholar’s heart. He distinguished himself in Latin in response to a challenge at Gray’s Inn. He turned aside from hunting to write his first poem, and wrote for his Inn the first prose drama ever produced in English, The Supposes. Next he gave us the second blank verse tragedy in the language, Jocasta. He wrote the first prose tale of modern life, the first tragedy in English from the Italian, the first masque, the first satire in regular verse, and the first English essay on poetry.

He furnished Shakespeare with part of the plot for the Taming of the Shrew, but was himself far from being a Shakespeare, or a great poet. He was lawyer, Member of Parliament, soldier, bankrupt, Court poet, and ambassador by turn, a licentious writer turned Puritan, lamenting his early errors and atoning in the famous satire The Steel Glass, a mirror held up to reflect the vices and virtues of his countrymen. He accompanied Queen Elizabeth to Kenilworth and wrote verses and masques in her honour. His life was full of adventure. He narrowly escaped shipwreck; he won honours in the field; he was surrounded at the head of 500 English by 3000 Spaniards, and was taken prisoner. On being released he came back to England but was sent out again on a mission, witnessed the sack of Antwerp by the Spaniards, and by his account of it (The Spoyle of Antwerp, Faithfully Reported) constituted himself the first English War Correspondent.

Flickr.

He must have been stirred by these ancient stones, the simple windows and doorways, and the judge’s seat inside the tower, where. we may sit today with the light falling through a Saxon window above us and look at this old church through the arch the Saxons made. Here Charles Kingsley’s two brothers were born, and here Charles became a poet. All through his life he kept the impressions made on him by this Fenland scene.

From the end of our first thousand years of history has come old Barnack Tower. The Normans preserved it but fashioned the church according to their own ideas, and the English who were fast absorbing their Norman invaders transformed the Norman church through all our great building centuries, and made it what it is. All these years the tower has stood unchanged, except that the Normans raised it another storey and the English gave it a stone steeple. It is certain that there is Danish influence in its carvings.

The Saxon tower rises in two stages with the familiar pilaster strips of stone running to the top on all sides. The stages are divided by a triple stringcourse, and above this on three sides are magnificent examples of Saxon carving, three rich panels of acanthus leaves in relief, all three with a bird on the top, and three other panels of ropework set in window openings. The lower stage has on the south a pure Saxon doorway, and above it a rounded window capped by a square moulding with two birds in the spandrels. The west window is one of the simplest Saxon windows we have seen, made up of seven stones crudely put together, but still as their builders left them a thousand years ago. Above this window is a much-worn head.

It was the Normans (doubtless working with the English that followed them) who added the third stage to the tower, an octagon with double window openings packed within eight-sided buttresses. The arches of the openings are all finely worked, each with three orders set on slender columns, a line of carving running up alongside each outer column. Over these arches a fine corbel table runs round the tower, and above it rises the sturdy-looking 13th century spire, completing as perfect a piece of Norman and Saxon work as we could desire.

The tower is as captivating within as without. The rough stones remain as the Saxons placed them, and in the west wall is a recessed stone seat which was brought to light in the middle of last century when the accumulated rubbish of many generations was removed. It is framed with great stones as used in a Saxon window, and it is believed that this seat is an old bench of justice, perhaps the oldest magistrate’s seat known in England, used by the President of the Court when justice was administered in this tower. In front of us as we sit in the old seat is the fine Saxon arch looking into the nave. lt is raised on simple stones in the true Saxon way, and the arch of two plain orders rests on the crudest of capitals; but it has stood while all the magnificence of our cathedrals has been rising in the land.

It is good to come into this church by its south porch, which is considered one of the best porches in all England, with its high pitched and vaulted roof covered with heavy stones, its wall arcades, and its lofty pointed entrance arch with finely moulded shafts and richly decorated capitals. It leads us to a great round doorway with dainty English shafts, elegant capitals, and row upon row of moulding in the arch. This noble porch was built by the English who followed the Normans. On the wall is a scratch dial.

The church carries on the traditions of architecture through all the styles it has known in our countryside, from the simplicity of Saxon days, through the grandeur of the Normans, into all the phases of our three English building centuries. In the nave the north arcade is 12th century and the south arcade is 13th, as is also the extraordinary clerestory, very low and with only a few small trefoil windows. The chancel is 14th century and its chantries are 15th.

The lofty northern arches of the nave are carved with the zigzag of the Normans, and their foliage and faces are on the capitals; the south arcade is Norman and English, still with the round arches that were passing away, but with the clustered columns and the stiff foliage capitals of the first English builders. Simple Norman carving is on their arch between the chancel and the north chapel. In the middle of the wall of the south aisle is a recessed tomb with fleur-de-lys, and on the wall of the north aisle is a medieval stone relief of Our Lord in Majesty, three feet long, the robe of a finely diapered pattern and still bearing traces of colour; it was found under the floor, and is an impressive piece of craftsmanship.

In the chancel is a triple sedilia with a curious sculpture on the moulding of the arch, a grimacing head with arms thrown back to grip the stone. The piscina here (among several medieval ones) has elaborate 14th century carving. On the north wall of the chancel is a Jacobean monument with painted figures of Francis Whetstone’s family at prayer; he died in 1612. The east window has in the tracery a few fragments of original glass, almost lost among the modern panels. There is a little more old glass in the priest’s room, showing a pope wearing a triple crown, a king, and a youth in a big collar. A good modem window in the south chapel has the Madonna in blue with a red robed and green-winged Gabriel below her.

The north and south chapels, added in the 15th century, both have ancient sculpture in them. In the south chapel, on the left of the east window, is a niche with a rare stone carving of the Annunciation, three figures in the clouds sending rays to the heart of the Madonna, who is kneeling at a prayer desk. It is a striking group set in a canopy, and has a village scene with a church in the distance. In another canopied niche on the right of this window is a modern Madonna and child. The altar table of the chapel is Jacobean, and is carved with the names of the Fallen in the First World War. In the north chapel is a tomb with carved and painted figures of a knight and his lady from Elizabethan days, and in another recess of this chapel are two battered figures 600 years old.

The font is unusual in shape and commands attention by its profusion of carving by the first English craftsmen. It is 13th century, and stands on eight open arches, looking rather primitive, as if the new style were struggling into being. Round the sides of the bowl are stiff rosettes, eight pairs, and above and below them are two bands of foliage. The cover is carved at its eight angles and crowned by the small figure of a child angel, with wings as big as itself. The pulpit and the screen are modern, the pulpit a good imitation of 14th century tracery, the screen with gilded figures of Mary and John, and a fragment of a medieval screen worked into it.

The church is built, of course, of Barnack Stone from the famous quarries known to the Romans and worked from the days of the Caesars until the end of the 15th century, when the Barnack Rag was exhausted. It was said in the old days that

Peterborough Minster would not have been so high

If Barnack Quarry had not been so nigh.

It is not surprising that in this quaint village the cottages should have medieval work built into them. One 14th century house has carved rosettes and another has a Saxon window.

The Kingsley Brothers

ALL the world knows Charles Kingsley and his Westward Ho! but his two younger brothers, though both brought distinction to the family, are less known. George Henry was born at Barnack Rectory in 1827 and Henry in 1830. We come upon Charles at Eversley in Hampshire where he lies. George entered on an adventurous life while still in his teens, and was wounded during the barricades in Paris in the revolution of 1848. He came back to England and at 21 was fighting an epidemic of cholera. His brother tells us of it in his novel Two Years Ago, where George Kingsley is Tom Thurnall. George was a brilliant talker, a keen sportsman, an enthusiastic field naturalist; and as he was familiar with many languages he travelled widely, and in his 65 years explored as many countries as almost any man of his time. He did much good literary work also, especially in editing manuscripts, and has another claim to fame as the father of the famous Mary Kingsley, who wrote so finely of her travels in West Africa and gave up her life as a nurse in a South African hospital at the time of the Boer War.

His brother Henry was a novelist and an editor during his 46 years, and he, too, travelled far, for he went to Australia when he was 23 and enjoyed his adventures in the Mounted Police. He wrote about twenty books, in which he put much of his experiences of the wild life of Australia, and few of our novelists have more faithfully sketched the best type of an English gentleman. His books are permeated by a fine spirit of romantic chivalry, and in this sense keep the high tone of Charles Kingsley’s books. As a journalist he went through the first war in which Germany attempted to subdue Europe, and after Sedan, when Napoleon the Third and his army were captured, Henry Kingsley was the first Englishman to enter the town.

A Founder of English Literature

GEORGE GASCOIGNE, sleeping in the vault of the Whetstones at Barnack, was one of the founders of English literature. Born at Cardington in Bedfordshire in 1525, he compressed into his 52 years activity enough for half-a-dozen men. A kinsman of Martin Frobisher, he shared the restless energy of his wonderful age, and plunged into the excesses that ruined many brilliant young men in Tudor London. But he had a scholar’s heart. He distinguished himself in Latin in response to a challenge at Gray’s Inn. He turned aside from hunting to write his first poem, and wrote for his Inn the first prose drama ever produced in English, The Supposes. Next he gave us the second blank verse tragedy in the language, Jocasta. He wrote the first prose tale of modern life, the first tragedy in English from the Italian, the first masque, the first satire in regular verse, and the first English essay on poetry.

He furnished Shakespeare with part of the plot for the Taming of the Shrew, but was himself far from being a Shakespeare, or a great poet. He was lawyer, Member of Parliament, soldier, bankrupt, Court poet, and ambassador by turn, a licentious writer turned Puritan, lamenting his early errors and atoning in the famous satire The Steel Glass, a mirror held up to reflect the vices and virtues of his countrymen. He accompanied Queen Elizabeth to Kenilworth and wrote verses and masques in her honour. His life was full of adventure. He narrowly escaped shipwreck; he won honours in the field; he was surrounded at the head of 500 English by 3000 Spaniards, and was taken prisoner. On being released he came back to England but was sent out again on a mission, witnessed the sack of Antwerp by the Spaniards, and by his account of it (The Spoyle of Antwerp, Faithfully Reported) constituted himself the first English War Correspondent.

Flickr.