First. All Saints, locked several keyholders listed - which is all well and good but when I fished out my phone I found it had died. Pevsner makes it sound worth a revisit.

It's a big church set in a lovely churchyard besides the Great Ouse and externally satisfying, particularly the tower. I look forward to an internal visit.

Next was the bridge with St Leger's chapel which is a delight and finally the Free church which isn't.

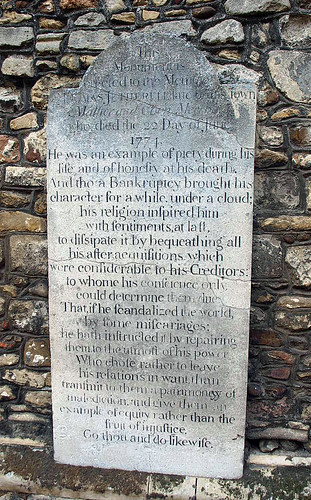

ALL SAINTS. In an enviable position by the Ouse and normally reached by a footpath from The Waits. It is a large church built mostly between c.1450 and c.1470, and its steeple is exceptionally fine in its proportions. The bell-openings are pairs of slender two-light openings, Perp, and the spire is recessed but has low broaches behind the battlements and pinnacles. Two bands run across it and contain the lucarnes, the upper ones being just quatrefoils. The W door is very elaborate, with two niches l. and r. The aisles and the chancel are also all Perp, except for the C13 N doorway with a hood-mould on head stops and the latest C13 S aisle E window of five lights with intersecting tracery broken at the top to allow for an encircled quatrefoil. Inside the S aisle is a splendid DOUBLE PISCINA with a surround of big dog-tooth. Each half has a pointed arch, but they are taken together by a round arch. The date could be as late as that of the E window, but is more likely to be earlier in the C13. The interior is as obviously Perp as the exterior. Arcades of high thin piers and thin arches; four bays. Against the piers a whole series of brackets for images, all decorated, some with foliage, one with a dog, another with a bull baited by a dog. High tower arch and tierceron-star vault in the tower. Embracing aisles. Two niches in the S aisle E wall. - FONT. Octagonal, Norman, with blank intersecting arches. - PULPIT. Elizabethan, with very elongated blank arches and panels with elementary geometrical motifs. - The vast ORGAN, in the Bodley tradition, is by Comper, 1893. - He also did the imitation-German STATUES on the brackets. - STAINED GLASS. Much by Wailes, also one window by Kempe, 1903 (chancel S) and one by Comper, 1896 (S aisle). - PLATE. Two large engraved Flagons of 1779-80; Processional Cross, Italian, C15 or early C16; bronze and brass Altar Cross, Venetian, c.1540. - MONUMENTS. Many tablets, e.g. a bulgy cartouche d. 1728 (a late date for the type). A tablet d. 1857 has a kneeling Hope by a Bible and an urn (also late for its type).

The BRIDGE is the most memorable monument of St Ives. May the temptation be resisted to sacrifice it to a through-traffic which should not at all rush along here. The bridge is still narrow and has preserved its cutwaters on both sides. It dates from about 1415. Midway along it is still a bridge chapel, one of only three in England, the others being Wakefield and Rotherham. The chapel is dedicated to ST LAWRENCE, and its altar was consecrated in 1426. It has an E apse and below the main room a lower one. No features or furnishings to report.

FREE CHURCH, Market Hill. By John Tarring, 1862-3. A fussy facade with not enough space l. and r. It is simply one of a terrace of buildings. Dec detail, embracing aisles, steeple of 156 ft. The interior with thin iron columns and no galleries. Just one unified room, but with an apse. Windows of three lights with geometrical tracery.

ST IVES. Every child knows it; it is the most famous town in any English nursery. We have all grown up with the man who, as he was going to St Ives, met a man with seven wives. It may be true or not, it may be this St Ives or the Cornish one, but what is true is that we did meet Oliver Cromwell in spirit and in bronze, and did see his old barn. We could wish the old barn had looked a little more healthy with so great a name to honour it; we found it in need of repair and seemed to hear a whispered hope that the National Trust would come this way and look at it. It is said that Cromwell drilled his soldiers in the barn and, as he mixed up religion with his farming, grew so poor that he had no farm left.

Here he stands in bronze on Market Hill, a country gentleman, a townsman of St Ives, his sword by his side and his Bible under his arm, pointing with his finger as if to say, Trust in God but keep your sword sharp. It is a splendid statue, which should, we understand, have been in Huntingdon but was not wanted by that town in those days. A thousand times he would walk over this wonderful old bridge with six fine arches, an 18th century red brick parapet, and a chapel in the middle, an odd and charming little place. We get the best peep of St Ives as we stand on the banks of the river, but we may go inside the chapel and walk down the stone steps and come out on the balcony. The chapel itself is but an empty shell.

St Ives is the last town on the Ouse before it enters the Fens; four wild swans greeted us as we arrived. Its great possession is its impressive church, a noble-looking structure with a soaring spire. We imagine it must be the only spire in England to have been brought down by an aeroplane. During the war a plane crashed into it; the spire fell through the roof of the aisle; the plane rested on the pews; the airman was dead.

The church has an arch of the 13th century, a chancel of the 14th, and a 15th century nave. The tower has a beautiful doorway with traceried spandrels and a carved frieze above it, and its vaulted roof has bosses carved with foliage and a pelican. Standing on brackets on the great pillars of the nave is a company of modern painted figures, among them the Madonna with a dragon on a chain and St George killing his dragon. The brackets on which they stand are old and gilded, and they have on them, carved by 15th century artists, such things as a lion’s face, a dog biting its tail, an eagle, a ram, and an angel. On the wall of the south aisle is a beautiful double piscina about 700 years old, a round arch enclosing two pointed arches springing from detached columns with carved capitals.

The 16th century oak‘ pulpit rests on a graceful trumpet-like stem probably older still; the pulpit is panelled and enriched with arches and side pilasters. The elegant font is 13th century, with arches running into each other. The reredos, crowned with angels, has four gilded wooden figures of evangelists and bishops with Christ in the centre. There are one or two fragments of 15th century glass, and two copies of Italian masters. The old chest dates from the beginning of the 18th century. One of the books kept in it has Cromwell’s signature as churchwarden. One of the bells of St Ives says, Arise and go to your business, and from another ring out two lines:

Sometimes joy and sometimes sorrow,

Marriage today and death tomorrow,

and it is said that they led indeed to the death of their founder, for the people were dissatisfied with his bells and went to law with him. He won his case but the excitement was too much, and he fell dead in mounting his horse to ride home. That was in 1723.

A gravestone tells us that

A crumb of Jacob’s dust lies here below,

Richer than all the mines of Mexico.

Who Jacob was we do not know, but St Ives has had more famous men. Here was born Robert Wilde, the shoemaker’s son who became a famous Puritan preacher; Thomas Ibbott, one of the early Quakers, who prophesied the Great Fire in the streets of London; Thomas James, headmaster of Rugby; and Sir Henry Lawrence, a Puritan statesman who was Cromwell’s landlord when he was a farmer at St Ives, and comes with high praise into one of Milton’s poems.

There are many quaint and narrow ways in St Ives, many fine peeps of the river, and an old house at each end of the bridge, a brick house of the 18th century and a woolstapler’s house 300 years old. But it would be hard in this old town, with all its enchanting places, to find a place surpassing in attractiveness the museum on the river bank. We have seen few museums built so neatly in so fair a place as this presented to his native town by Mr Norris, the successful business man of Cirencester who loved his old town of St Ives and all his life collected treasure for it. Perhaps we may think its best possession is the peep from the window along the river to the spire of the old church, but in truth the new museum is filled with old entrancing things. There are old books bound at Little Gidding by Nicholas Ferrar’s community, little ships made by Napoleon’s prisoners from the bones they saved at their meals, and a domino set made by them in a box they made with straw. There is a leather water-bottle like Cromwell’s bottle at Hinchingbrooke, a letter written by Cromwell, and a portrait of him by a foreign artist who has painted him with a feather in his hat.

St Ive is little known in history, but 900 years ago a monk wrote down and improved local traditions concerning him. It is believed that he may have been a Persian bishop, who with three companions made his way to this country by Rome and Gaul. So great was the reverence he inspired that the Gauls sought to keep him among them, but he pressed on to Britain. Here this poorly clad and ill-favoured newcomer began a campaign against idolatry, St Patrick being among his first converts. In those days St Ive was known as Slepe, and it was here that he carried on his missionary work for many years. Here he was buried.

The next we hear of him is 400 years later, when a labourer at the plough discovered the saint’s grave in a field. That night St Ive appeared to another man in a vision, bidding him go to the Abbot of Ramsey and tell him to lift the body from the ground. The remains were duly removed to Ramsey with much ceremony, and a priory church was built on the spot where the body was found. Thus round this spot was founded the town of St Ives. The saint was popular, for, says the medieval chronicler, “there is not any in England more easy of prayer or more helpful than St Ive.”

Here he stands in bronze on Market Hill, a country gentleman, a townsman of St Ives, his sword by his side and his Bible under his arm, pointing with his finger as if to say, Trust in God but keep your sword sharp. It is a splendid statue, which should, we understand, have been in Huntingdon but was not wanted by that town in those days. A thousand times he would walk over this wonderful old bridge with six fine arches, an 18th century red brick parapet, and a chapel in the middle, an odd and charming little place. We get the best peep of St Ives as we stand on the banks of the river, but we may go inside the chapel and walk down the stone steps and come out on the balcony. The chapel itself is but an empty shell.

St Ives is the last town on the Ouse before it enters the Fens; four wild swans greeted us as we arrived. Its great possession is its impressive church, a noble-looking structure with a soaring spire. We imagine it must be the only spire in England to have been brought down by an aeroplane. During the war a plane crashed into it; the spire fell through the roof of the aisle; the plane rested on the pews; the airman was dead.

The church has an arch of the 13th century, a chancel of the 14th, and a 15th century nave. The tower has a beautiful doorway with traceried spandrels and a carved frieze above it, and its vaulted roof has bosses carved with foliage and a pelican. Standing on brackets on the great pillars of the nave is a company of modern painted figures, among them the Madonna with a dragon on a chain and St George killing his dragon. The brackets on which they stand are old and gilded, and they have on them, carved by 15th century artists, such things as a lion’s face, a dog biting its tail, an eagle, a ram, and an angel. On the wall of the south aisle is a beautiful double piscina about 700 years old, a round arch enclosing two pointed arches springing from detached columns with carved capitals.

The 16th century oak‘ pulpit rests on a graceful trumpet-like stem probably older still; the pulpit is panelled and enriched with arches and side pilasters. The elegant font is 13th century, with arches running into each other. The reredos, crowned with angels, has four gilded wooden figures of evangelists and bishops with Christ in the centre. There are one or two fragments of 15th century glass, and two copies of Italian masters. The old chest dates from the beginning of the 18th century. One of the books kept in it has Cromwell’s signature as churchwarden. One of the bells of St Ives says, Arise and go to your business, and from another ring out two lines:

Sometimes joy and sometimes sorrow,

Marriage today and death tomorrow,

and it is said that they led indeed to the death of their founder, for the people were dissatisfied with his bells and went to law with him. He won his case but the excitement was too much, and he fell dead in mounting his horse to ride home. That was in 1723.

A gravestone tells us that

A crumb of Jacob’s dust lies here below,

Richer than all the mines of Mexico.

Who Jacob was we do not know, but St Ives has had more famous men. Here was born Robert Wilde, the shoemaker’s son who became a famous Puritan preacher; Thomas Ibbott, one of the early Quakers, who prophesied the Great Fire in the streets of London; Thomas James, headmaster of Rugby; and Sir Henry Lawrence, a Puritan statesman who was Cromwell’s landlord when he was a farmer at St Ives, and comes with high praise into one of Milton’s poems.

There are many quaint and narrow ways in St Ives, many fine peeps of the river, and an old house at each end of the bridge, a brick house of the 18th century and a woolstapler’s house 300 years old. But it would be hard in this old town, with all its enchanting places, to find a place surpassing in attractiveness the museum on the river bank. We have seen few museums built so neatly in so fair a place as this presented to his native town by Mr Norris, the successful business man of Cirencester who loved his old town of St Ives and all his life collected treasure for it. Perhaps we may think its best possession is the peep from the window along the river to the spire of the old church, but in truth the new museum is filled with old entrancing things. There are old books bound at Little Gidding by Nicholas Ferrar’s community, little ships made by Napoleon’s prisoners from the bones they saved at their meals, and a domino set made by them in a box they made with straw. There is a leather water-bottle like Cromwell’s bottle at Hinchingbrooke, a letter written by Cromwell, and a portrait of him by a foreign artist who has painted him with a feather in his hat.

St Ive is little known in history, but 900 years ago a monk wrote down and improved local traditions concerning him. It is believed that he may have been a Persian bishop, who with three companions made his way to this country by Rome and Gaul. So great was the reverence he inspired that the Gauls sought to keep him among them, but he pressed on to Britain. Here this poorly clad and ill-favoured newcomer began a campaign against idolatry, St Patrick being among his first converts. In those days St Ive was known as Slepe, and it was here that he carried on his missionary work for many years. Here he was buried.

The next we hear of him is 400 years later, when a labourer at the plough discovered the saint’s grave in a field. That night St Ive appeared to another man in a vision, bidding him go to the Abbot of Ramsey and tell him to lift the body from the ground. The remains were duly removed to Ramsey with much ceremony, and a priory church was built on the spot where the body was found. Thus round this spot was founded the town of St Ives. The saint was popular, for, says the medieval chronicler, “there is not any in England more easy of prayer or more helpful than St Ive.”

Flickr.