ST BOTOLPH. Permission for the rebuilding of the church was given by the Abbot of Peterborough to Sir William de Thorpe in 1263-4. Nave and aisles and bellcote. No structural division between nave and chancel. The windows have pointed-trefoiled lights; the W window has a quatrefoiled circle over its two lights. Wide nave of three bays. Slender circular piers with circular capitals and abaci. Single-chamfered arches with hood-moulds. - PLATE. Cup and Paten, 1817.

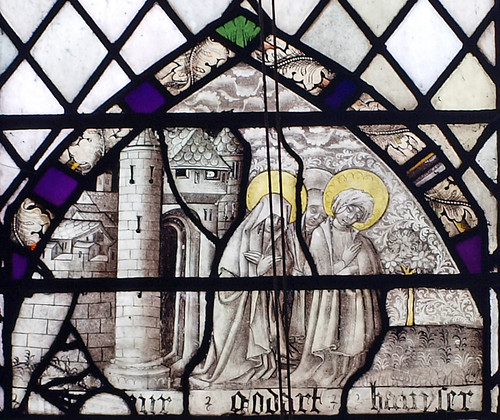

LONGTHORPE TOWER. About 1300 the tower was added to a late C13 hall. The hall survives, but has no internal features of interest. The N window is of two lights divided by a shaft and has a quatrefoil in plate tracery. Access to the ground floor as well as the upper floor of the tower was only from the hall, not from the outside. The tower is square, and has walls 6 to 7 ft thick and square turrets on the comers. The windows are small, of single lights, with trefoiled heads or shouldered lintels. Some early C17 alterations. The ground-floor room has a quadripartite rib-vault. So has the room on the principal floor. The ribs are single-chamfered and stand on corbels. The second-floor room has no vault. It is reached by a straight staircase in the thickness of the S wall. The outstanding interest of Longthorpe Tower is the WALL PAINTINGS in the principal room, which were discovered only after the Second World War. They date from c.1330 and are more extensive than any of so early a date in any house in England. Subjects are taken from the Bible, as well as moralities such as the Three Quick and the Three Dead. Also a monk teaching a boy (the inscription here is in French), the Wheel of the Seven Ages of Man, the Wheel of the Five Senses (figured as animals), the Labours of the Months, and plenty of birds and flowers. In the vault figures of musicians and the Signs of the four Evangelists.* As for the style, it has been compared by Mr E. Clive Rouse with such somewhat earlier illuminated manuscripts as Queen Mary’s Psalter and the Bestiary at Corpus Christi College Cambridge.

* A detailed description will be found in the leaflet published by the Ministry of Public Building and Works.

LONGTHORPE. The cathedral city has begun to swallow it up, and Longthorpe is part of Peterborough, but it survives with an individuality of its own. At one end it has a small fortified 13th century house, and at the other is the historic Thorpe Hall, which Mr Alfred Gotch described as halfway between Elizabethan and Georgian.

A path shaded by fine trees and rambler roses brings us to the fortified house, a strange combination of an ancient and modern home, inhabited for about 700 years. The old staircase has gone, and a modern part has been added as a wing to the high embattled tower. The square doorway with a heavy nail-studded door remains, and there are wide buttresses between the windows. The one tower now standing is all that remains from the troubled and turbulent days of Edward the First; it is used as a house.

Thorpe Hall, at the end of the village nearer the city, is one of the few notable houses built during the Commonwealth, the artist being John Webb of the school of Inigo Jones, whose son-in-law he was. The influence of the master is clearly seen in the general style of the building. It is thought that the materials may have come from the ruins of the cathedral cloisters. The Hall once belonged to Oliver St John, the moderate man who quarrelled with Cromwell and took the side of General Monk at the Restoration. A wide avenue of limes leads us to the handsome gateway of this house, bronze eagles being mounted on the great stone posts, which are carved with heads of lions. Balustraded steps lead to the entrance with round columns which support a balustraded gallery. In the courtyard are some noble cedars and evergreen oaks.

The little church on the roadside has purple clematis and crimson creepers climbing its grey stone walls, and a medieval statue has been set on the roof of a new building outside the south aisle. The chancel, nave, and aisles are much as they were when the builders left them in the 13th century. There is a 13th century piscina, and a memorial shrine in memory of the men of the First World War; the altar rails are also in their memory. Hanging on a 13th century column of the graceful arcades is the translation of a deed dated 1623 providing for the rebuilding of a chapel here.

A path shaded by fine trees and rambler roses brings us to the fortified house, a strange combination of an ancient and modern home, inhabited for about 700 years. The old staircase has gone, and a modern part has been added as a wing to the high embattled tower. The square doorway with a heavy nail-studded door remains, and there are wide buttresses between the windows. The one tower now standing is all that remains from the troubled and turbulent days of Edward the First; it is used as a house.

Thorpe Hall, at the end of the village nearer the city, is one of the few notable houses built during the Commonwealth, the artist being John Webb of the school of Inigo Jones, whose son-in-law he was. The influence of the master is clearly seen in the general style of the building. It is thought that the materials may have come from the ruins of the cathedral cloisters. The Hall once belonged to Oliver St John, the moderate man who quarrelled with Cromwell and took the side of General Monk at the Restoration. A wide avenue of limes leads us to the handsome gateway of this house, bronze eagles being mounted on the great stone posts, which are carved with heads of lions. Balustraded steps lead to the entrance with round columns which support a balustraded gallery. In the courtyard are some noble cedars and evergreen oaks.

The little church on the roadside has purple clematis and crimson creepers climbing its grey stone walls, and a medieval statue has been set on the roof of a new building outside the south aisle. The chancel, nave, and aisles are much as they were when the builders left them in the 13th century. There is a 13th century piscina, and a memorial shrine in memory of the men of the First World War; the altar rails are also in their memory. Hanging on a 13th century column of the graceful arcades is the translation of a deed dated 1623 providing for the rebuilding of a chapel here.