I was amazed to find All Saints locked with no keyholder listed [and without a church notice board] - why? you may ask and I would explain that it's naturally locked by an unfathomable one way system, which any potential thief would find hard to decode, and that it sits in a very busy pedestrianised square where any malpractice could not fail to be noticed.

Whatsoever - it's locked and Pevsner doesn't make it sound too interesting but, and keep in mind that I know nothing about Huntingdon or its populace, what sort of message does a lockdown church send to the expectant visitor? I've found open churches in rougher parts of London that should make the incumbent hang his, or her, head in shame.

ALL SAINTS. Along the Market Place. The E end is close to the High Street. The church is varied in outline and fits well into its surroundings. The tower is placed at the corner. It was set into an existing building, as its S wall stands on the first bay of an E.E. N arcade, the oldest remaining feature.* That it was an arcade and not a tower arch is evident from the fact that the W respond of the arch is a respond indeed - it has stiff-leaf decoration - but that the E respond is simply a round pier with an octagonal abacus. The upper parts of the tower are of brick, rebuilt after the Civil War, and the very top is Victorian. Otherwise the church is essentially Perp, except for the N aisle windows, which with their crocketed arches and tracery look Dec, and the organ chamber and vestry, which are by Sir G. G. Scott, of 1859. The organ chamber is the prettiest feature of the church, with its angel at the apex playing on a positive organ. The arcades, of four (on the N side of course three) bays, are characteristically Early Perp. Piers of standard moulded section, arches of two sunk-quadrant mouldings, the arch tops slightly ogee. The E window of the S aisle has mullions carried down blank to form a reredos. In the SE corner charming niche on a foliated corbel and with a canopy. Good Perp chancel roof with carved bosses. - STAINED GLASS. The clerestory windows are of 1860, by Clayton & Bell. - By the same the former chancel E window, now in the W wall of the S aisle. It shows the Te Deum in the presence of Prophets, Apostles, and Saints, and also the Venerable Bede, William of Wykeham, Archbishop Cranmer, Bishop Ridley, George Herbert, Newton, Handel, Queen Victoria and Prince ‘Albert, and the Duke of Weflington. - The W Window is by Kempe, 1900 (with his wheatsheaf). - The E window is by Tower, Kempe’s successor, c.1920. - PLATE. Flemish Chalice of c.1750; silver-gilt. - MONUMENT. Alice Weaver d. 1636. Tablet with kneeling figures in relief. The top has already - very early - an open scrolly pediment. - Good Victorian CHURCHYARD RAILINGS.

* But some N walling is Norman.

HUNTINGDON. Its streets have resounded with the tramp of Roman legions. The Saxons set a castle on the little green hills at the back of its square. The Normans built the school where Oliver Cromwell and Samuel Pepys both went as boys. Little can the people of Huntingdon who would see these boys playing in their streets have imagined that one would raise England to the height of power beyond the dream of kings, and that the other would leave behind him a picture of the life of England to be read for centuries.

It is enough to give a town a sense of great importance, yet Huntingdon makes no pretence to greatness; it is just an old-fashioned place where many things have happened. It has not thought it worth while to set up a statue of Oliver Cromwell at one end of its street and a statue of Pepys at the other; it was not until the other day that this old town had a single record in stone of the fact that it gave Oliver Cromwell to the world.

Milton’s Chief of Men, our greatest man of action, was born at the bottom of Huntingdon’s long street. The long brick wall is here as it has been for centuries, for it was the boundary wall of the Augustinian Priory, and in the garden over the wall Cromwell would play in his boyhood. It is all there is to see of his birthplace as he knew it, for his house has gone. It is possible that part of the house now standing here may belong to the birthplace, and certainly much of the old materials was used; and it is certain that Cromwell’s garden was bounded by these brick walls. There is an arch that he would walk through, and, however changed the scene may be, it was here that that life began which shook the English throne, established securely the fame and freedom of our people, and gave history for all time a man to wonder at.

We walk about the scenes of his boyhood. He would walk from here along this street to the little Norman schoolroom facing the church in which he was baptised. The record of his birth and baptism are in the registers at All Saints, and there his father lies. Here his mother is not, for Oliver was to take her up to the Palace of Whitehall and lay her at last in the loveliest shrine in London, the Chapel of Henry the Seventh, where a dissolute king was to dig up her remains and throw them into a pit.

It is believed that she had great influence with Oliver in his early days. The story is that he was the terror of the neighbourhood, living a wild life, so that the ale-wives of Huntingdon were afraid of him. When the time came that his means would not allow extravagance (and especially when his rich Uncle Oliver at Hinchingbrooke became displeased with him), the brewer’s son changed his ways and gave way to his mother’s persuasions.

We may think that the little school looking down on the pavement of this long street is the most intimate Cromwell monument we have. It stands on the Roman way called Ermine Street, and it has still looking into the street a magnificent Norman doorway, a Norman window, and a row of five Norman arches. It is thrilling to us not only as a piece of Norman England, the hall of a 12th century hospital which became in time the grammar school of Huntingdon, but because to this little place came two boys whose names are famous throughout the world, Oliver himself, and Pepys. Pepys spent some of his boyhood in a village near by, and lived to see the great Oliver’s head stuck on a post at Westminster Hall, and to write in his diary that night that he did see this thing and did think it an indignity for a man so great.

Oliver’s father is described as having been extremely careful with his education, first putting him under Mr Long, a minister of Huntingdon, and then removing him to the grammar school under Dr Beard. It is stated somewhere that the boy had fits of learning, “now a hard student for a week or two, then a truant for a month or two, and of not settled constancy.” It was during his schooltime here that he was flogged by Dr Beard for telling the story of a vision in which he saw a gigantic figure opening the curtains of his bed and declaring that he should be the greatest person in the kingdom. Whether that be true or not, it appears to be true that during his schooldays here the comedy of Lingua was played and nothing would satisfy Cromwell but the part of Tactus. The idea of the comedy, which was first printed in 1607 and first acted at Trinity College, Cambridge, is a combat between the Five Senses for superiority, and one of the scenes in the first act is a conversation between Tactus and Mendacio, during which Tactus fumbles with a crown:

Tactus: A crown and robe!

Mendacio: It had been better for you to have found a fool ’s coat, and a bauble.

Tactus: Tis wondrous rich: ha! but sure it is not so: Do I not sleep and dream of this good luck?

Then comes a scene in which Tactus is soliloquising:

This crown and robe,

My brows and body circle; and invests,

How gallantly it fits me, sure the slave

Measured my head that wrought this coronet,

They lie who say complexions cannot change,

My blood’s ennobled, and I am transformed

Unto the sacred temper of a king.

Methinks I hear my noble parasites

Styling me Caesar, or great Alexander,

Licking my feet, and wondering where I got

This precious ointment, how my pace is mended,

How princely do I speak, how sharp I threaten:

Peasants, I’ll curb your headstrong impudence,

And make you tremble when the lion roars.

It is believed that Huntingdon rejected the statue of Cromwell now standing in St Ives, but its mayor and corporation made amend by giving their blessing to the stone set in 1938 by the Norman doorway, recording the fact that Cromwell attended this school. It is the only memorial of Cromwell in the town, and was presented by the Cromwell Association in a speech by Mr Isaac Foot and unveiled by the Earl of Sandwich, who arranged for its beautiful heraldic carving to be copied from the badge on Cromwell’s leather water bottle, which is now at Hinchingbrooke, the superb Tudor house of the Cromwells a mile away.

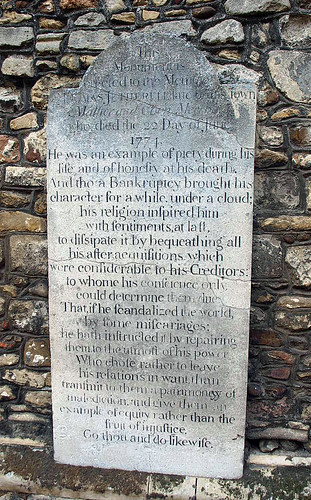

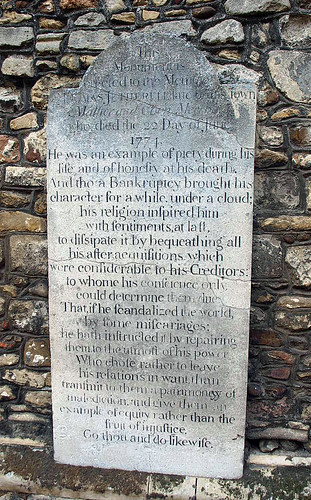

Looking across at this stone from the walls of All Saints Church is another curious stone, engraved in the 18th century with a moral lesson for all who pass by. It is to Thomas Jetherell, a maltster who died in 1774 and is declared to have been an example of piety in life and honesty in death. Bankruptcy brought his character under a cloud, but religion inspired him to bequeath all his acquisitions after that (which were considerable) to his creditors, so that if he scandalised the world by some miscarriages he repaired them to the utmost of his power, choosing to leave his relations in want rather than transmit to them a patrimony of malediction, rather giving them an example of equity than the fruit of injustice.

All Saints is one of two fine churches in Huntingdon; it has two old churches and two old inns. The churches are medieval, and the inns are 17th century. The Falcon has a cobbled courtyard with a long window over the gateway, and the George has a picturesque galleried yard with an oak staircase leading to a painted balcony.

The stately south front of All Saints looks out on the marketplace, an impressive background for the little square with its great aisle windows, the clerestory receding above, and the 14th century tower beyond. It has richly sculptured walls, a pinnacled and battlemented tower of the 14th century, and buttresses guarded by figures under canopied niches. The church is mainly 15th century. Inside, the eye is drawn by the beauty of the old chancel roof, its cornice carved with small faces, the beams adorned with tiny winged angels in gold, while eight great angels reach out from the walls looking down on the musical angels crowning the stalls. Everywhere on this roof are roses and crowns and stars, flowers and knots and shields, and bearing up the beams on the walls are wooden figures of saints resting on brackets of grotesque creatures in stone. Under this roof there rested for a night the body of Mary Queen of Scots on its way from her old grave in Peterborough to her new grave in Westminster Abbey.

The font at which Cromwell was baptised is older than the church it stands in; the bowl is 13th century, set on a new arcaded stem. The stained glass windows which darken the church have kneeling apostles, saints, and martyrs, including a Roman matron, St George and St Pancras, and men carrying models of Ely and Lincoln Cathedrals. The clerestory windows have 21 painted saints. Over the doorway in memory of Alice Weaver is her kneeling figure in alabaster, with her husband and six children; she would be stirred by the news that her famous townsman was leading the fight of the Parliament against the king.

St Mary’s Church comes from all our great building centuries, the chancel 13th, the tower and the west porch 14th, the clerestory 15th. It has at two corners of the south aisle fragments of Norman buttresses from which it is clear that the Norman church on this site must have been of great size. The chancel walls were raised when the clerestory was built in the 15th century; the north arcade of three bays was refashioned with the old material 300 years ago; the south arcade is the original 13th century. The tower is magnificent with pinnacles, a band of decoration below its battlements, and a charming doorway with a canopied niche on each side. About 600 years ago somebody scratched a drawing of a bell on one of its stones and the winds and rains of centuries have left it clear. In the south wall is a beautiful doorway through which priests have passed about 700 years.

The church is crowded with interest and beauty; it has a remarkable collection of small things. Hanging on the west wall is a group of flags among which is one captured from the Sikhs in 1846, a Boy Scout flag hanging with the flag flown in the Great War by HMS Walpole, and three fine banners made in Bruges. There are hanging lamps copied from old Italian and old Spanish lamps, two oak chests restored in the 17th century, two high-backed walnut chairs of Restoration days, an Elizabethan chalice, a 200-year-old copy of Guercino’s Holy Child, and a tiny fragment of a 14th century screen which is all that is left of the vanished church of St Benedict. In the south chapel are carved wooden figures and a beautiful Madonna in plaster, and in the north chapel is a fine gilt figure with outstretched arms, carved in wood by a craftsman in a Belgian village. One of the altars has a frontal of‘ great beauty made in Bruges, showing the angels bringing the good news to Mary. The chancel altar rails are by J. N. Comper, the gold angels on the uprights coming from Austria.

Set in the wall by the 13th century chancel arch is a small stone deeply cut with the names: R. Cromwell, I. Turpin, Bailiffs 1609. High above the chancel arch are four ancient figures carved out of solid oak about the end of the 15th century. They show four apostles, Stephen, Bartholomew, Jude, and Matthew, all carrying the Gospels and their emblems—flaying knives, a boat, and a carpenter’s square. Few small towns are more interesting out of doors than Huntingdon. It has fine old houses, stately churches, deserted churchyards, a noble bridge, an 18th century town hall extended just after Waterloo; the 18th century house in which the poet Cowper lived; the 17th century Walden House (now used by the County Council) with some 16th century woodwork; an 18th century house built by the Ferrars of Little Gidding with a little stained glass of Stuart days; the great ancestral home of the Cromwells, and, of course, the famous mound on which the ancient castle stood. We see it from the bridge which shares its fame as part of the oldest spectacle in this old town. The bridge, from which we see Huntingdon at its best, leads on to the great Causeway which links the town with Godmanchester. It is one of the loveliest stone bridges in England, as good a piece of stonework as the 13th century has left us, with carving over some of its arches, and with bays to protect the traveller from the dangers of its narrow way. From it we look across to the spacious green meadows with the great mound, the elegant spire of Trinity Church rising above the roofs behind. Not far from where we stand is the long graceful house fronting the street, with dormers and a central pediment, where William Cowper came to live with "the most agreeable family in the world.”

Cowper came to Huntingdon in the summer of 1765, finding himself very soon on good terms with “no less than five families, besides two or three odd scrambling fellows like myself.” One of them was the Unwin family, destined to have so great an influence on his life; another was a North Country parson who travelled on foot 16 miles every Sunday to serve his churches, and who invited Cowper to supper on bread and cheese and a black jug of ale of his own brewing. Another friend the poet met was a thin, tall, old man as good as he was thin, drinking nothing but water and eating no meat, and to be met every morning of his life at 6 o’clock at a fountain a mile from the town. His great piety, said Cowper, was equalled by nothing but his great regularity: he was the most perfect timepiece in the world. As for Mrs Unwin, he met her in the street and went home with her and they walked for two hours in the garden, having a conversation which “did me more good than I should have received from an audience of the first prince of Europe.” He knew also the woollen draper, “a healthy, wealthy, sponsible man”; he had a cold bath and had promised the poet the key of it.

In the little market square on which the 12th century grammar school, the 15th century church, and the 18th century town hall look down, stands one of the best of all our peace memorials, a monument in bronze which somehow reminded us of The Thinker by‘Rodin; it is by the widow of Captain Scott (Lady Kennet), and shows a soldier sitting with his head resting on his hand. Four centuries have given something to this heart of Huntingdon, and here have stood these famous men who belonged to this small place: Cromwell, Pepys, Cowper. But the roll begins earlier and ends later than these, for Henry of Huntingdon wrote a 12th century history of England, and Sir Michael Foster, one of the greatest physiologists who ever lived, was born here on the eve of the Victorian Era and lies in the cemetery. He sleeps not far from where he first opened his eyes, but most of his long life he was away, though he joined his father’s Huntingdon surgery for a few years in the sixties of last century. At 31 he began teaching physiology in University College, London, and a few years later left for Cambridge, where Huxley recommended him for a post. He presided over the British Association, went into Parliament, founded a scientific society, and wrote a famous text book.

The Cromwell House at Huntingdon has vanished except for the bricks of its walls, which may be its successor; but the Cromwell House of Hinchingbrooke, where it is believed Oliver had his first encounter with Charles, remains in all its glory just outside the town.